|

Let’s talk about the white elephant in the classroom The post “There is no place for computers in early childhood” on my ‘Dance with me in the Heart’ facebook page set off one of the most lively conversations since I launched the page in November 2012. The title of the post is an accurate statement, intended to attract readers’ attention. Nature needs nurture Now that I have your attention, let me explain why there is no place for computers in the child’s early years. What happens in the young child’s developing mind-brain-body when she uses computers interferes with what is supposed to happen in a young child’s mind, brain and body. Just one consideration is movement. Movement in those early years builds the brain. It literally constructs the brain using body-mind-brain sequences trialled and fine-tuned over thousands and thousands of generations. Educational kinesiologist Carla Hannaford states, “Movement is the architect of the brain”, and you know what happens when someone has a stroke in the brain. The body is affected because body and brain are indivisibly connected. Being in front of a screen precludes the movement that builds brains. Novelty is a brain hit The human (brain) loves novelty, and that is one of the drivers behind the curiosity of the young child. It is that curiosity that generates the child’s exploration, rolling, touching, smelling, tasting, balancing, moving, jumping, comparing, weighing..., all of which build not only the brain (as important as that is), but contribute to building a literal body of knowledge unique to that child. Every body of knowledge is unique to the individual because the connections-skills-competencies that are developed, are dependent on the experiences the individual has. It is the human brain’s love of novelty that assures infants and young children will physically follow their curiosity and explore everything in their environment. Novelty in information technology Who could fail to be impressed with the novelty within the range of information-technology hardware available? Who could fail to be impressed by the functions and capabilities of the different devices, and similarly impressed by the vast range of programs-apps available for those computerised devices? It truly is mind boggling. No doubt about it, information-technology hardware and software designer-engineers are good. They know how to serve up the novelty required to keep aficionados wanting to upgrade, which not coincidently, keeps the shares of their respective corporations afloat. Novelty: the two-edged sword Normal human fascination with the novel capabilities of technology drives much of the push to have computers as a major factor in every child’s ‘education’, from tertiary where it is a most suitable tool, to early childhood where it couldn’t be more unsuitable. Like it or not, there will also be a commercial element behind this push to have computers introduced in the early years. Research shows children’s buying behaviours are largely set by age 6-7, so product allegiance at an early age is not something manufacturers will have overlooked. Further, if teachers can be persuaded that information-technology has benefits for early childhood, those same teachers become the agent of persuasion to others within their profession. Child magic wins And that is what has happened. Teachers who are fervent about the capabilities of the technology have omitted to look beyond the magic of the device toward the magic of the young child. In their delight in the technology, teachers have overlooked

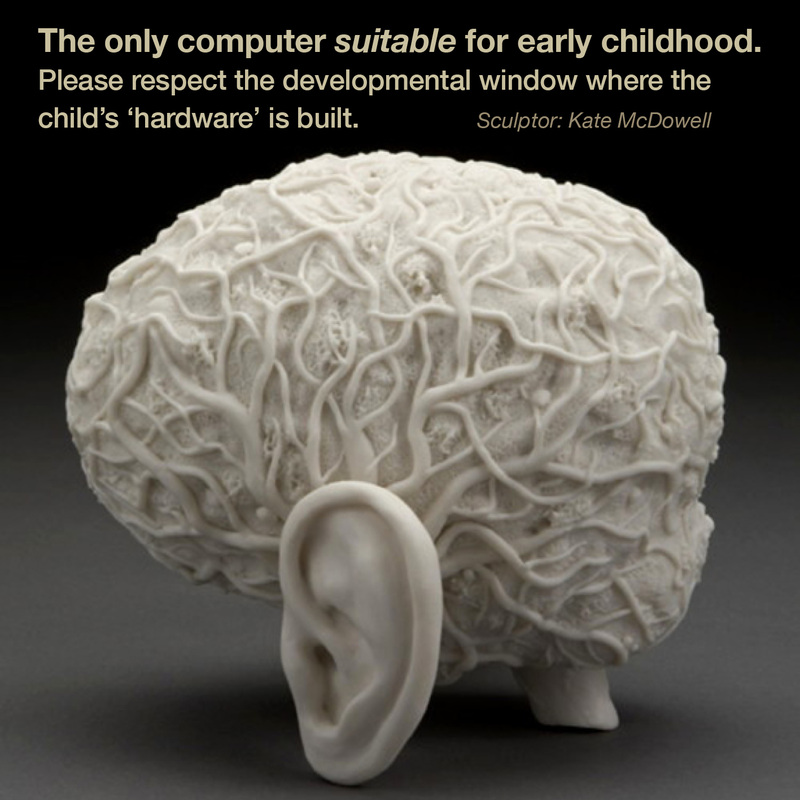

Child-centred not skills-based The arguments put forward by those who exhort the use of computers in early childhood do not line up with the requirements for young child’s unfolding, and/or are based on ‘logic’ and research about the competency/skill-sets that can be gained by very young children using computers. There is no denying that young children can build up impressive computer skills. Indeed, young children have baled out many tech-illiterate parents and grandparents with their expertise. However, it is the role of education professionals to have the child’s wellbeing to the fore and weigh up the benefits of the learned competencies-skill-sets-expertise against the developmental priorities of the human child - mind, brain and body. It is not that computers are ‘bad’ (hell no, I love my Mac); the issue is about age and developmental appropriateness. Start with the hardware The brain is the hardware, the original ‘computer’. Computer ‘nerds’ don’t try to run software while the hardware is still under construction, and the young child’s brain (hardware) is under construction. At birth the brain is 25% of its adult size, by three years it will be between 85% - 90% of its adult size. Construction happens in the brain when the child interacts in the world in three dimensions - not in two dimensions. A two dimensional screen encounter is, by definition, impoverished in sensory input. There is not enough sensory information with which to construct a body of knowledge involving multiple senses and multiple intelligences. The child must interact with their mind, brain and body. That is how they are designed. In computer terms, you wouldn’t expect brilliant performance from a compromised operating system running on a miniscule amount of RAM. 3 is the magic number At three years of age the actual brain construction is almost done. That is one of the reasons the first three years of the child’s life are so important, the bulk of the child’s hardware is built, complete with individualised default settings. The child uses the next three to four years installing the programs that three dimensional living and playing provide free with each child, all of which will be the exact right platform to launch into the next phase/mode of information processing in the neocortex at age 6-7. These three dimensional play programs prepare the way for the neocortex to handle abstract symbolic learning. It is beyond me why education professionals would risk compromising and/or damaging this exquisite genetically fine-tuned design by introducing 2D technology when it is not age appropriate? What is the hurry? The real world rules There is general confusion among teachers about learning in the real three dimensional (3D) world, and in the virtual two dimensional (2D) world. When children play in the real world with all of their dimensions (physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual - at least), they use all of their senses (19 recognised so far) to build a body of knowledge. This ‘body of knowledge’ that they ‘build’ is quite literal. The intelligence of the body learns how to do whatever it perseveres with: eg. to balance, crawl, sit, walk, or to deliver an ace of a tennis serve, or to become the barista who can use the coffee machine and make an awesome flat white - while the other barista who uses the same coffee machine makes rejects every time. One barista can learn while the other barista is slow on the uptake. Why? Like all learning in the real world, barista learning is learning in all dimensions. 3D learning includes the body intelligences, which take into account details like the grind of the bean, the humidity in the air, the temperature of the milk, the duration of each phase... and on and on. In the real world the choices are many - maybe even infinite. Playing and operating in the real world is the way people learn how to learn. A child is a spirit, in a body, who feels, and thinks - in that order So important is this practical body of intelligence that according to play researcher Stuart Brown, JPL (Jet Propulsion Laboratory) NASA and Boeing will not hire graduates for their research and development teams, no matter how great their degrees, nor how prestigious the university that awarded the degrees, unless the applicants have done things with their hands, made things and fixed things, like making rafts, building flying foxes, pulling apart toasters and fixing cars. People who have not worked with their hands cannot problem-solve in real life, and this because the hand and brain are linked in ways neuroscientists believe to be seminal to the actual structure of the neocortex - the great thinking human brain - and in its development. So get out the clay, the sellotape, the flax and the cardboard... our children should be making things in three dimensions, in the real world, ideally up until they are eleven years old when yet another cognitive shift occurs. 3 beats 2, exponentially 2D learning is just that - working in two dimensions (width, length - but no depth - literally and metaphorically) with predominantly 2 senses (hearing and sight), with binary choices. Yes, computers are ‘clever’, yes, even very impressive - and they are not the real world, they can only offer a virtual world. Even a ‘3D screen display’ is a 2D optical illusion. Virtual is an adjective meaning, “not physically existing as such, but made by software to appear so”. In a virtual world you cannot be there; you can only learn about it. It is little wonder most educators are confused and think computers are great. Schools rarely do experiential learning which would enable students to build for themselves a body of knowledge so critical for learning and problem solving. Rarely do teachers facilitate a real experience so their students can make knowledge from ‘the doing’ for themselves. Most commonly, we teachers task our students to ‘learn’ about things - i.e. google it/find it in a text/watch a video. In other words, we task them to seek information, to see what others have done-thought-felt. That’s the difference between having a delicious Middle Eastern meal - and reading the recipes. No comparison. The screen-spread virus in the human brain’s abstract-symbolic ‘processor’ All abstract symbolic metaphoric higher learning depends on the ability to think in images, and not only two dimensional images, but to think with the whole body of knowledge recalling every dimension of the image. For example, if I say ‘aardvark’ (the stimulus) your response will be as good as your experience of aardvarks. For some there will be no response at all, but for most of us we’ll recall a two dimensional image of an aardvark we saw in a text or on a screen. Among us, someone might have (improbably) kept an aardvark as a pet, and that person will have a body of knowledge about aardvarks. That person will know their habits, actions, communication vocalisations, reactions, smell, movements, bowel movements, texture of skin, of fur-hair... and on and on. It is all of THAT knowledge which is the aardark keeper’s rich and instant response in the mind-brain-body to the stimulus of the word ‘aardvark’. Now extrapolate out of that example and you will understand why computers short change young children who are just getting to explore, know and understand being here on this three dimensional planet. Further along in the child’s education teachers will speak about poultry, thrust, centrifugal force, thermodynamics, metamorphisis etc. The child, who may have picked up all sorts of information about those topics in front of a screen, simply cannot have the knowledge from which to work in the abstract in a meaningful way. Keeping hens, riding the zip wire, self induced giddiness, spinning with a full bucket of water, lighting fires, growing swan plants - real life living in three dimensions - that is what sets children up for the abstract symbolic processing we call reading, writing, and numeracy. After all, reading and writing are just recording in a way to stimulate the brain to recall-synthesise-amalgamate-create data from the body of knowledge existent. When the virus is deadly

You and I take it for granted that when someone offers a stimulus - e.g. the word ‘hedgehog’ - the brain will automatically offer a response and provide an image. If the child is lucky and did the real-life-3D-get-to-know-hedgehog-thing, the image-response will be multidimensional. What most early childhood teachers overlook is that this stimulus-image response is a learned skill, which every child can learn, as long as the conditions are right. So what are the right conditions that enable the brain to set itself up for imagining, creating and processing abstract symolic information? I have written an article that goes into this in more detail, but here is a short version: three dimensional experience builds up a body of knowledge which includes the actual images of the experience being available ‘in’ the brain. Children are curious and get into everything, so they build up heaps of images available in the brain. Are you still with me? Then when someone speaks (stimulus) about the little red hen (three stimuli there: little, red, and hen) and the grains of wheat (stimulus), the child calls up her images (response) of little, red, hens and wheat from her experience, and sets about moving-combining-synthesising her own images into a creation so she can make sense of the story/stimulus. Try this: maz sarkans vistu. No response? It isn’t the right stimulus for English speakers, maz sarkans vistu is Latvian for little red hen. This stimulus-response function is pure brain alchemy, and all higher learning is dependent on this function. There is a window for the brain-alchemy function The child isn’t born able to do this, the brain is not complete enough at birth. The child has to prepare and install this function through their exploration and play. In other words, the brain develops this function during a biologically determined window of time. Miss the window and the child (and society) is in serious trouble. This window happens to be in the early childhood years. Until recently this particular stimulus-response brain function has always been developed and installed like clockwork, but not any longer. There are many children who have so much screen time that the process is stymied. These children don’t develop the stimulus-response function, and to understand why that is, we need to look at how screens differ from real life. When I say to you, “the little red hen”, your brain responds to the stimulus with images. When the screen says to you, “the little red hen”, the screen (stimulus) supplies its own response; the image of the little red hen is there before you on the screen. There is nothing for your brain to do: no retrieving, no connecting, no synthesising, no creating... no growth and no development. Too much of this for a young child and the window is missed, and closes. Encepholograph readings of people watching screens read very close to brain dead, there is nothing for the brain to respond to. That’s fine if you want to blob out in front of a screen, but it is not fine for the human child building the functions of her ‘brain processor’, functions which will decide her ‘computing’ capabilities. Justification is the art of telling ourselves stories so we’ll feel better doing dodgy things One argument put forward by the pro-technology-in-early-childhood lobby is that we need to introduce computers at an early age because, like it or not, we are living in the age of technology. True. Many infants and children know what it is to be sidelined by their parents in favour of phones, screens, and/or computer games, and children learn to use whatever technology they are surrounded by. Almost every child comes from a home where there are smart phones, MP3 players and computers, and many spend the bulk of their waking time being entertained in two-dimensions. What these children lack is enough time living and playing in the 3D world. Too little screen time is not the burden of today’s child; quite the reverse. The ‘we use it as a tool’ story This week I have spoken with teachers who are enthusiastic about computers as tools - me too, this program I am working in now beats handwriting for speed any day. But for teachers to say computers encourage research skills, curiosity and creativity in early childhood is justification at best, and disingenuous at worst. There isn’t an child who has to be encouraged to research, to be curious or to be creative - they are all born that way. Young children just have to touch, they use all of their senses to get to know what they examine, they are fascinated. What we have to do is make sure they stay that way by ensuring their environment is as rich and harmonious as possible. Such an environment is always going to be in the three dimensional world. Sorry, a 2D tablet simply won’t cut it. Computer engineers, programers, designers wanted: Apply if you are 7 or older Children who meet computers/screens after they have turned seven will have all the time they would need to become first class computer nerds because of the cognitive shift that occurs at 6-7 years. That shift enables the brain to engage in the mode of functioning where the two dimensional abstract virtual world of computers becomes an appropriate field of play and learning. The few computer nerds I know started on a Commodore 64 in their teens. It was early enough. As for the argument that ‘children love them’, they love chocolate biscuits and cartoons too. That doesn’t mean a diet of chocolate or screens is good for them - or us. Both are addictive and addictions take us away from engaging in the rich living which Life offers. Age and stage appropriate Legality aside, we wouldn’t let a child of ten drive a car on the open road even if they could (and some can) because it is not age appropriate. We don’t start teaching children to drive before they are 15, even though they could learn, because there is no need to teach them until it is age appropriate. Instead, we use that freed-up time to offer/facilitate learning opportunities that are age appropriate. Let’s use the same restraint and wisdom with information technology. Don’t be sucked in Early childhood is not school - don’t be fooled-wooed into thinking your children need technology at your place. They don’t. Use this precious window in each child’s life to support their 3D Play in Real 3D Life. (References for this blog are listed in the PDF, see under 'Articles '.)

4 Comments

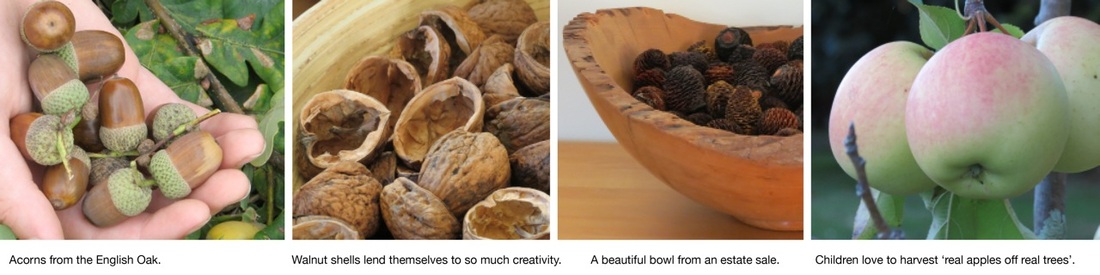

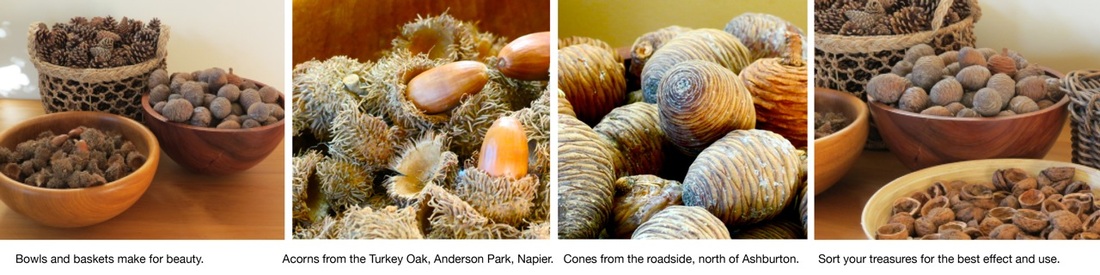

Autumn Sale of Superior Educational Equipment To those of you who are fascinated by superior and amazing learning materials for our children, this is your season. Nature's harvest in the Autumn doesn't stop at pumpkins, apples and feijoas; educational equipment is also part of the harvest. As is usual with Nature's abundance and generosity, her harvest won't cost you anything more than the time it takes you to harvest it. Just as they have done for thousands of years, children express their in-built, genetic patterns of 'being human' with these treasures. Not surprisingly, the patterns children express using multiple natural materials lay the platform for literacy and numeracy. The child's urge (humans urge) to sort, order, pattern, group, connect, classify, seriate..., these patterns of play are the physical prerequisites for the more abstract versions of the same skills that will come on stream later: (3X3) X (4+13). There are other bonuses when we use natural materials instead of bought plastic stuff. These natural items themselves are the epitome of the mathematical patterns nature employs in creation, affording our children the chance to 'down load' these patterns, as well as the subtleties of colour, texture, smell and sound. Much of this play and learning happens naturally, outside, as in days of old: in the sandpit with the shells, under the trees with the acorns, in the hedge with the leaves.... Inside is a second best as far as most children are concerned, but objects of beauty inside add harmony and beauty - think of photos in the House and Garden magazine. Beautiful Containers for Beautiful Materials Even though the equipment comes for free, there will be a cost - you will have to source some beautiful containers to store your treasure. Beautiful baskets and wooden bowls can be found for bargain prices at garage sales and opportunity shops. A wooden bowl that is stained is easily sanded then oiled back to its original glory. If you want sets of containers, Trade Aid is a good place to look, a place where you know your dollar is doing more good than you thought a dollar could do. Baskets, Heuristic Play, Exclusion and Inclusion

I hadn't heard the term heuristic until about twelve years ago. I couldn't guess from the context what it meant, so instead of pretending I understood, I owned up; "What does that mean?" Turns out, the person using it wasn't too sure what it meant either, so I went home and looked it up. Heuristic [Hyoo-ris-tic, or, often yoo-] Adjective a: serving to indicate or point out; stimulating interest as a means of further investigation b: encouraging a person to learn, discover, understand, or solve problems on his or her own, as by experimenting, evaluating possible answers or solutions, or by trial and error - an heuristic teaching method c. of, pertaining to, or based on experimentation, evaluation, or trial and error methods. When you look at the definition, most of our learning in life is heuristic. 'Heuristic' does not apply exclusively to the infant 'treasure baskets' people tend to be referring to when they use this term. I am not in favour of those of us in early childhood using the term 'heuristic' - except in assignments - because jargon is exclusive, it excludes those not in the know. Using the word heuristic in conversation with parents, or in learning stories that parents will read, leaves most parents either wondering what on earth are 'they' are talking about. The parents who want to understand what we are talking about will have to ask us point blank, "What does that mean?" At that point they can feel included. Beauty and Education Beauty needs to part of every child's education, and all of the great educators understood this, from Plato, through to Steiner, Montessori (oh those beautiful geometric shapes), Loris Malaguzzi... and You. Two quotes from Plato: "The object of education is to teach us to love what is beautiful." The mathematical patterns of this earth are stunningly beautiful. Nature is always works in patterns: from the pattern of an atom, of a molecule, of a cell, of a crystal, of a shell, of a walnut... "The most effective kind of education is that a child should play among lovely things." Human Beings - Human Doings In this time of high stress for parents, babies, children, and teachers it is time to reevaluate what we want for our children and for ourselves from our education system. Part of the solution will be remembering the balance between being and doing, and then working to achieve that. Education and Cultural Imperatives Education as we know it is a cultural activity, and different cultures have different takes on what works and what doesn’t. For example, the education practices of Japan and Korea could not be more different from those of Sweden and Norway if they had planned it that way. That’s because cultural activities are always ‘man-made’, and sometimes they line up with how people are designed and how they work, and often-times they don’t. What about Biological Imperatives? Training people to work in the education industry is likewise a cultural activity and is ‘man-made’. Sometimes what we are taught - and how we are taught - lines up with how we ourselves are designed and learn, and most often it doesn’t. Moreover, almost without exception, what we are taught is not in line with how children are designed nor how they learn. It not that the information about age-appropriate biologically-neurologically-compatible teaching and learning isn’t available, it is. It’s just not taught in most education pre-service training, including Early Childhood pre-service training, and the consequences for the child under three are dire. If you are set on measuring, then unseen-reality poses a bit of a problem I believe that one of the reasons for the mismatch of biological imperatives and cultural imperatives is our compulsion to measure, especially when it rubs up against our bias against the unseen, the ‘spiritual’. ‘If it can’t be seen and measured it doesn’t exist’ seems to be the underlying mantra. Tell that to someone who is contented, curious, excited, full of wonder, in love, relaxed, or confident. These are all aspects of reality, and I would argue, they are better indicators of a successful programme than anything you can measure. It is nigh impossible to measure something you cannot see like children’s happiness; it is too hard to quantify, too hard to evaluate it’s worth empirically, and this might be the genesis of murmurings from individuals in the ERO who want a more prescriptive early childhood curriculum. It would make it easier for them to measure. Being or doing? Traditionally, teachers have been trained in skills of ‘doing’ to the exclusion of skills of ‘being’, the skills of the unseen, skills of the spirit. Our pre-service training drills us in how to ‘do’ teaching, and included in the teacher’s tool kit are the ‘doings’ of teaching, extending, planning, scaffolding, questioning... We have been modelled these behaviours - these ‘human doings’ - and we have been taught them. As a result, we often end up believing that these skills are what being a teacher is all about. To add to their legitimacy, there are rules and regulations which enforce these cultural imperatives: you have to do it or you could be mentioned in your workplace report as noncompliant and/or not ‘up to scratch’. The ethic of reciprocity - How would I like it? But what if these skills and behaviours (as valuable as they can be), block the child in her learning? What if these cultural imperatives are a poor match for the biological imperatives of the child? If we were to put ourselves into the learner’s shoes and ask ourselves, “How would I like it?” we would get a better idea about what is appropriate, and when. Let me do it If you or I were learning something that was new to us, we’d want to take our time. We’d want time to ponder, to figure it out - then try it out. If it didn’t work the first time we would try again. We’d try to figure out another way and then try that out. It depends on how much stickability we had developed as learners how long you or I would keep this ‘figure-it-out-try-it-out’ pattern going, but most of us keep going until we get it. Or until we are stymied. If we achieve it, there is such a sense of joy and wellbeing. If we are stymied then - and only then - we ask for help. And we only want as much help as we ask for, we don’t want the ‘teacher’ to take over and do it for us. This pattern of discovery is the age old human pattern that is also known as learning. It’s a species thing, it’s good for all ages of homo sapiens sapiens. We are born curious, and if we get a fair go, we want to try things out and discover how they work, in real time, in real life, not in assignments.

Too often what is deemed scaffolding, open ended questioning, extending and teaching does not facilitate the independent experimentation Emmi Pikler is talking about. Too often it is adult intrusion and leads children to learn the practice of 'brain-borrowing'. Brain borrowing is when the child takes all the cues and scaffolding to achieve something they wouldn’t have achieved independently, at least not at that time in that way. For example -

“What would happen if you turned it around? Would it fit then? Keep going. That’s the way, that way looks like it could work. Try that.” From teacher to educator This is an extreme example, but my guess is that we have all done it sometime during our journey towards being an educator rather than a teacher. That journey asks us to become skilled in Human Being, so that we know when to apply the human doings, and how to apply them in ways that allow the child the satisfaction of making her own knowledge. Pennie Brownlee • October • 2013 Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts. Albert Einstein Paintings: Top left - Adriana Mufarrege. Top right - Morgan Weistling. Bottom right - Sayda Afonina |

Author

Still a believer in the printed word - does that make me a fossil? Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed